An Exhibition in cooperation with HAUNCH OF VENISON, London

T-shirts emblazoned with red five-pointed stars and baseball caps with hammer and sickle logos; bags featuring portraits of Gagarin and KGB-themed watches; mugs decorated with portraits of revolutionaries in the style of Mayakovsky and the must have fashion item for several seasons, Red Army cloth caps: all these as well as many more everyday items decorated with exotic Soviet symbolism could be found weighing down the shelves of souvenir shops worldwide in the late 1980s. Gorbachev’s policy of liberalising Soviet society provoked a universal fashion for ‘glasnost’ and ‘perestroika.’ These two words, unfailingly pronounced in a heavy Anglo-Saxon accent, took the world by storm, enriching the fundamental lexicon of pop-culture as they went.

The ‘red wave’ that flooded the West was born long before Gorbachev’s economic and political reforms. The aesthetics of designing impressively bright and large-scale sets for the latest in a series of ideological revolutions grew up in the deep underground of socialist counterculture, in the world of unofficial art in Moscow and Leningrad. Whereas for the overwhelming majority of Soviet citizens the freedom to do and say what they wanted came as a complete surprise, artists welcomed it with open arms. It was they who designed the set for the raising of the iron curtain, drawing all the hard-won achievements of prohibited art.

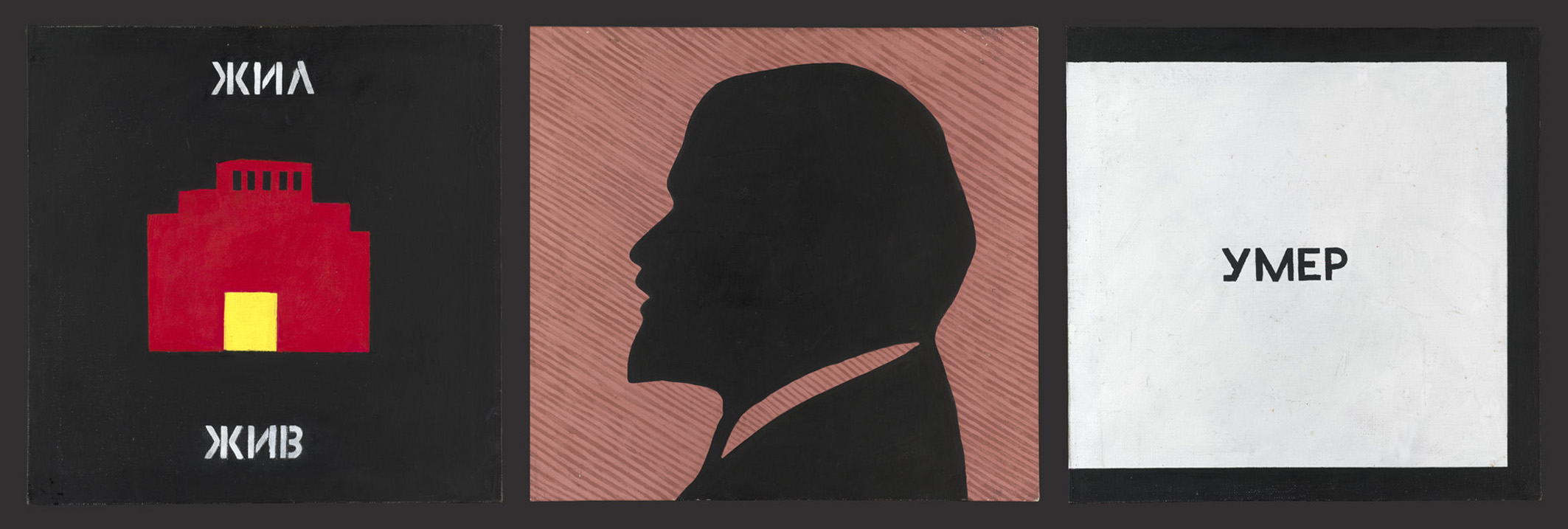

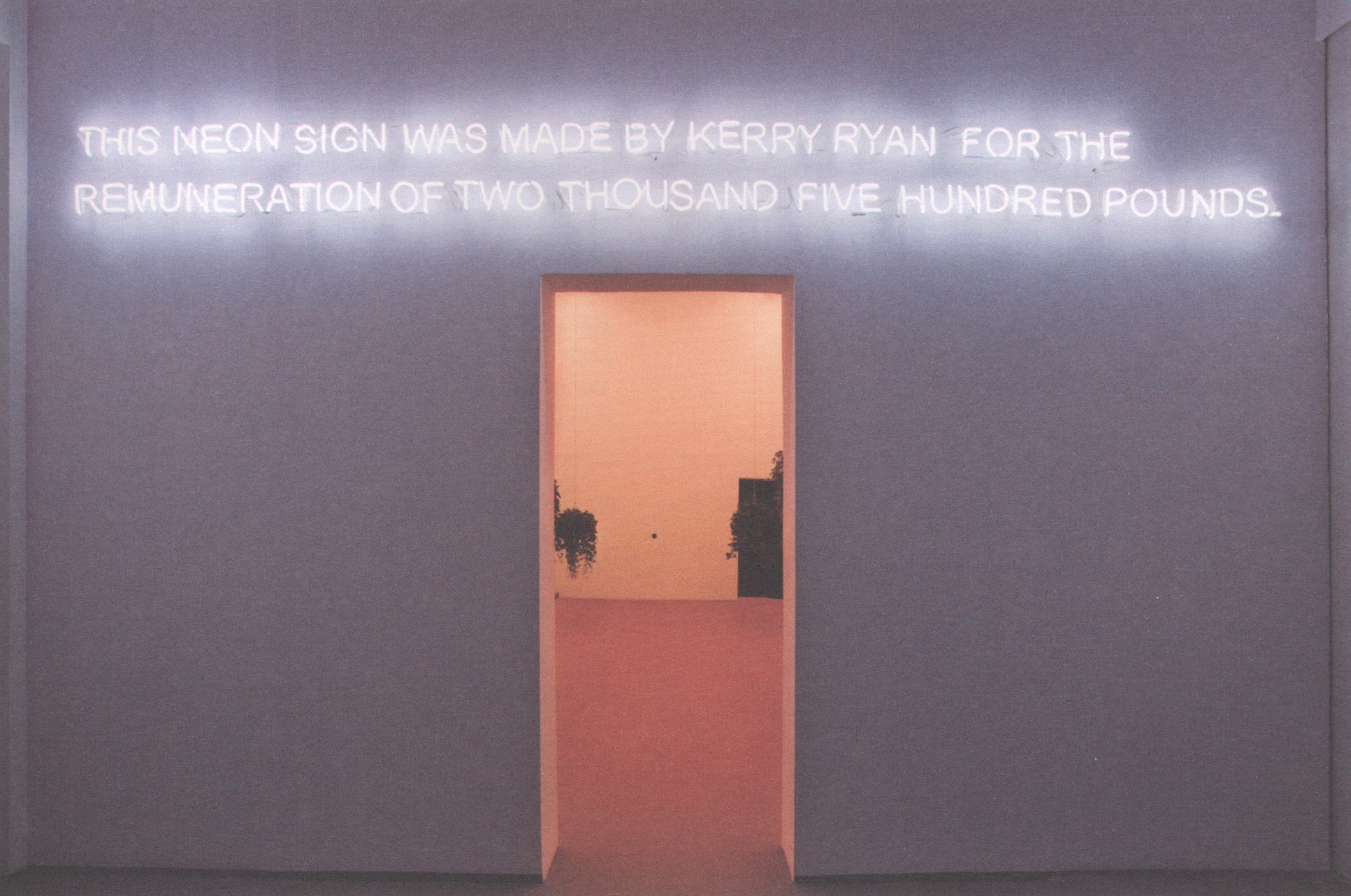

They were all different: they came from different schools of art, took inspiration from different artistic authorities, loved different colours and styles. Some continued in the glorious tradition of Sots Art, with its biting irony and deadly fear. Others were conceptualists, ‘lawful artists,’ comprehending all the subtleties of the intellectual manipulation of mass consciousness. A third group tried to speak out without a soviet accent, looking to European contemporary art as the only source of genuine relevance. Yet another group enriched the borrowed languages of the German Junge Wilde and the French Figuration Libre with vignettes of almost-forgotten homegrown history: suprematist geometry and constructivist design.

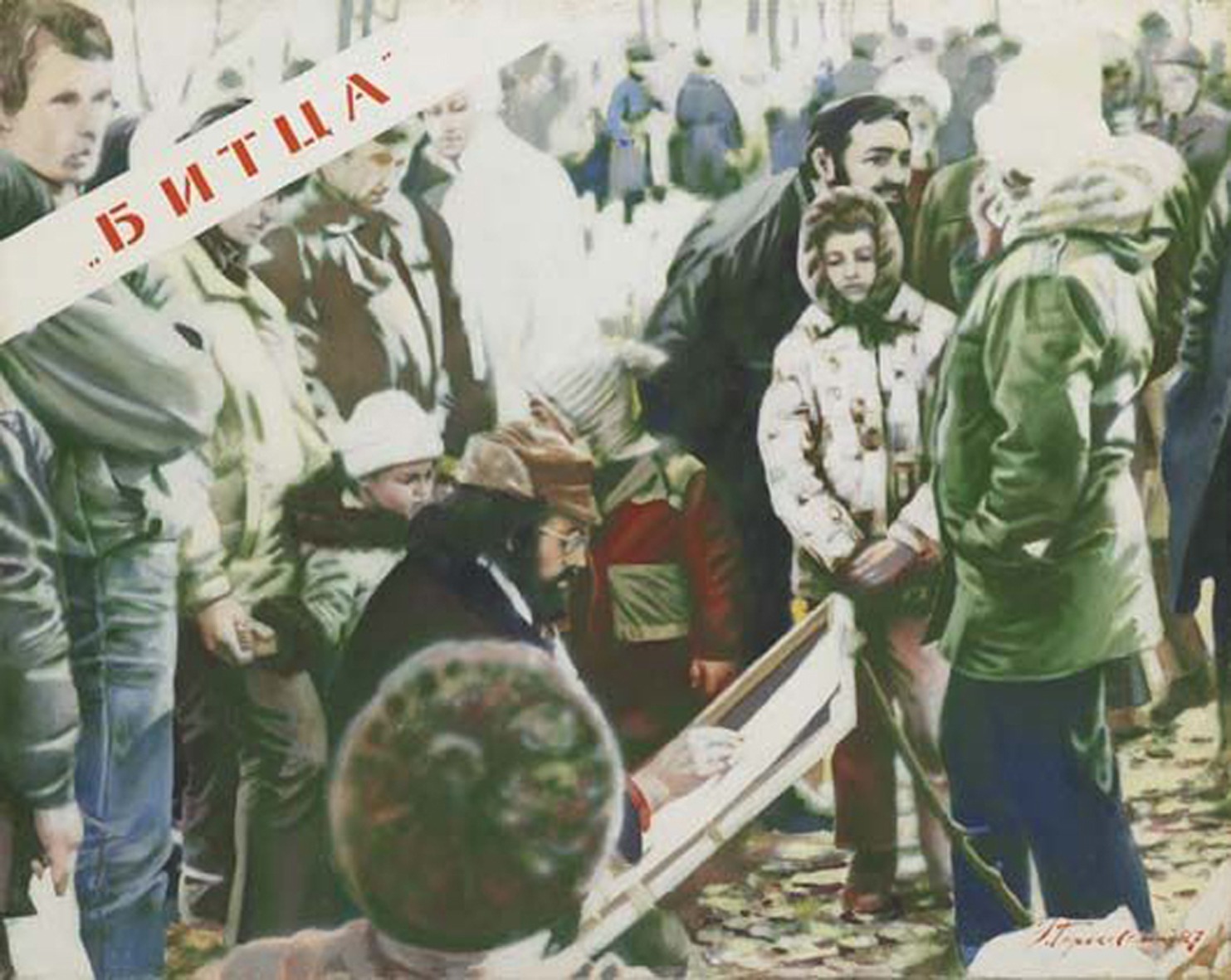

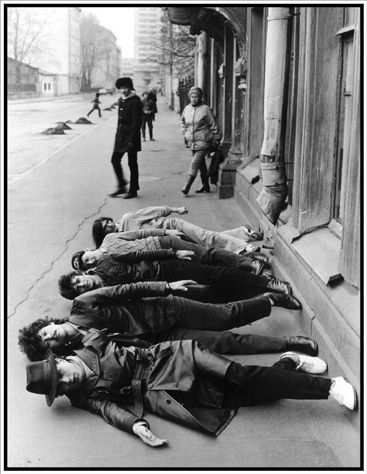

Their paths crossed at the first public exhibitions of this legendary era. ‘Youth exhibitions,’ shows organised without the permission of the artists unions, multi-media performances in the Moscow and Leningrad ‘palaces of culture,’ and later tours to museums and exhibition halls from Berlin to New York and from Tel-Aviv to Melbourne – it was in these places that the visual language of modernity was born and the new face of Russian art was formed. Opposites met and fused seamlessly, turning the bland routine of artistic process into a universal carnival on the ruins of an empire.

The meeting point for individual styles and artistic movements was Sergei Solovev’s cult film Assa, which hit Soviet cinemas in 1987. This eclectic cocktail of belated Sots Art, amusing conceptual tricks and laid-back St. Petersburg new wave is seen today as the archetypal piece of ‘perestroika art.’

In this we can find the truth about the triumph of the ‘Soviet avant-garde’ of the late 80s, in the general euphoria that accompanied the abandoning of basements and attics and the setting out to conquer the international art scene. Under the fashionable label ‘Made in the USSR,’ the public was introduced to the work of veteran nonconformists, their young but already experienced pupils from the Moscow school of conceptualism, the Leningrad ‘new artists,’ young talent from the studios of Furmanny street, photo-realists and ‘paper architects.’

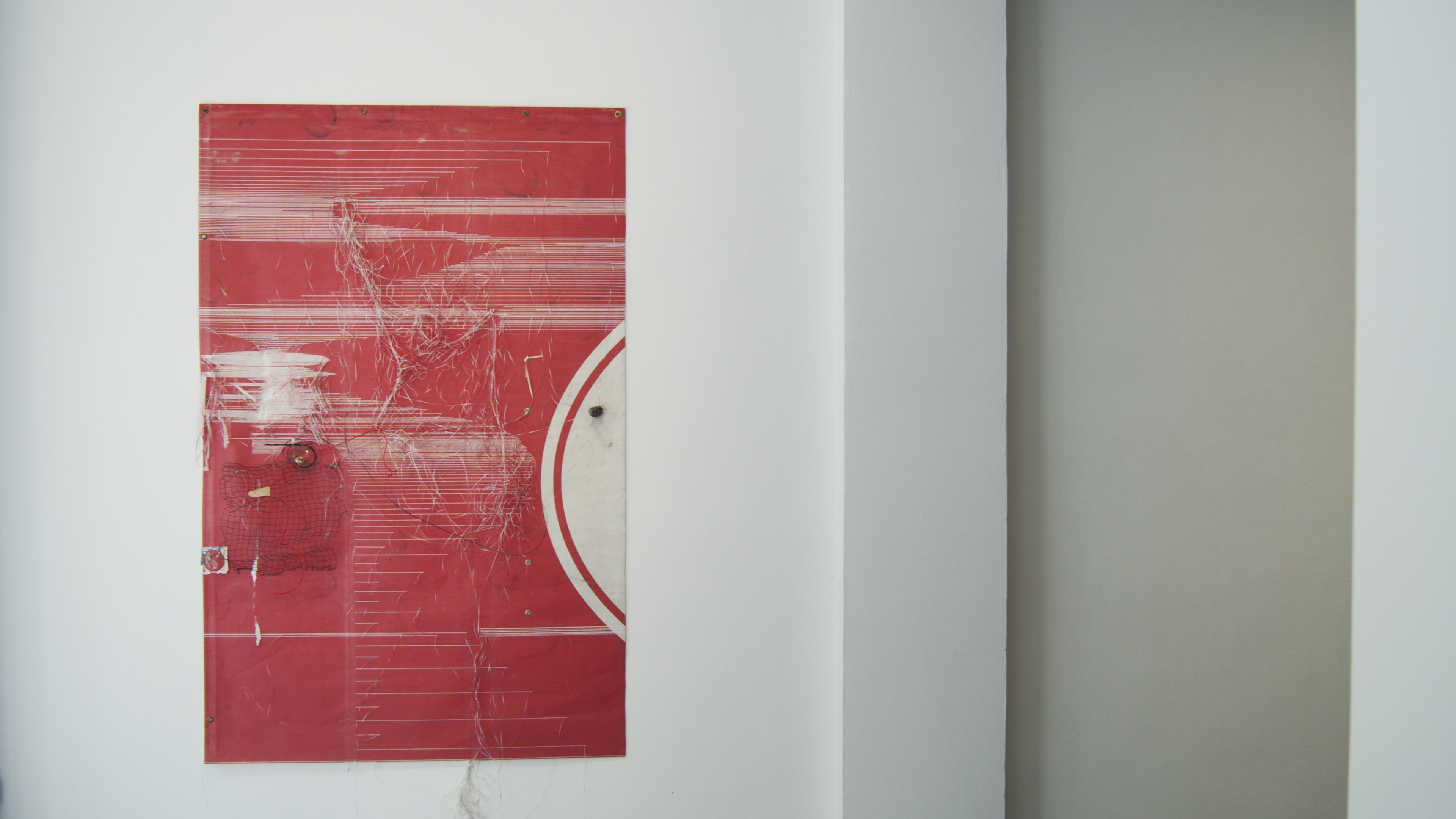

The curators of this exhibition have gathered in one collection paintings, sculptures, installations and photographs in an attempt to reconstruct and analyse the historical context ‘perestroika art’ and convey the inimitable aura of a period of change, presenting the work of its original heroes – Ivan Chiukov, Eduard Gorokhovskovo, Igor Makarevich, Semyon Faibisovich, Sergey Volkov, Sergey Mironenko, Vadim Zakharov, Nikolai Kozlov, Andrey Filippov, Maria Konstantinova, Nikolai Ovchinnikov, Sergey Shutov, Andrey Reuter, Timur Novikov, Andrey Khlobystin, Sergey Borisov, Andrey Bezukladnikov, Alexander Sundukov, and Igor Chatskin.